The Chaparral 2H

The mystery of the lost chassis....

An intriguing theory, busted or confirmed? And Jim Hall's answer!

As a Chaparral enthusiast since 1971 (yes, they had unfortunately just vanished from the circuits by the time I could read English) the only thing I could do (and dedicatedly did) was collecting magazine articles about the Midland Magicians. And remarkably, my Chaparral files (over 50 cm's of bookshelves of torn out ancient magazine articles) show a lot of interest of the motor racing press in all the Chaparrals and their heritage during the years of running and in retrospect. My favourite model, the Chaparral 2H, however, was always rather poorly documented in magazines. Its reputation as the least competitive Chaparral was maybe due to this lack in press coverage. And so it became the most mysterious of the breed.

Thanks to a few good books about Chaparral and the Can-Am series, released in recent years, I started to get more obsessed by this slippery piece of soap on wheels. So up until now, much more has been written about the 2H and I've got a lot of answers to my questions. But, at the same time, I've got the uneasy feeling that much still has not been written about the 'White Wale' and, on top of that, many new questions raised:

- Where are the fuel fillers for example?

- Or: is there any photograph of the front suspension?

- And: who came up with the De Dion suspension idea?

- Who actually designed the very advanced body of the car?

- What was the exact role of Chevrolet R&D?

But as the most mysterious question emerged: Have there possibly ever been two 2H chassis instead of the believed one?

Maybe it's time to ask Jim Hall, founder of Chaparral, a question or two. And I'd better hurry because although the man is immortal (and I hope he is in good health), he and Troy Rogers (his faithful mechanic since the sixties) are maybe the only persons left on earth who know the real story behind the 2H.

Maybe I'll end up with the famous dry smile of Jim Hall saying his "I suppose there will always be these little Chaparral secrets." But at least I can give it a serious try in order to add an essential piece of history to a car, worth every inch and rivet.

Most instrumental to my research on the 2H is the book "Chevrolet = Racing..? Fourteen years of raucous silence!!" by Paul van Valkenburgh. It was published in 1972, just three years after the 2H racing season. It is famous and most sought after now. Paul started writing about racing cars when he became technical editor of Sports Car Graphic magazine after a career as aerodynamics engineer at Chevrolet's Research & Development department in the sixties.

I bought the book in 1984 and I still remember vividly the excitement rising when, in chapter 4, all the highly astonishing stuff was revealed about the secret relationship between Chaparral and Chevrolet's R&D.

To me it's not quite clear when Van Valkenburgh exactly started as an engineer at Chevrolets' R&D. But in this book he recalls somewhere that he was "recently acquired as 'department aerodynamicist" when the wing of the Chaparral 2E (to be raced in 1966, the first Can-Am season, author) was developed. He was involved in wind tunnel research. In April 1966 he was "startling visitors at the Tech Center with a Stingray coupe carrying a monstrous wing mounted on struts two feet above the rear window".

So, probably he was an employee at Chevrolet R&D since 1965 or spring '66. He stayed there for three years and a half. In retrospect it is very likely that he had a deep insight in the Chaparral/Chevrolet relationship during the development of the 2H. So I consider him as an authority on this subject.

As I said, at last a few books about Chaparral have been published in recent years. I still cannot understand that the world had to wait more than twenty years for a book about this fabulous racing brand! I was even convinced for many years, that I (as an amateur!) was the one human being destined to write the history of the Texan roadrunners because nobody else did. Luckily some professionals stepped in at the right moment and their books were a great source of information in addition to my magazine files.

Elementary knowledge about Hall, Chaparral and the 2H

Jim Hall was a Texan driver/engineer in the sixties, founder of one of the most intriguing brands in motor racing history. During the sixties, his name was synonymous with original thinking and advanced concepts. His cars won many races but lost even more. He was the kind of guy who said: "when nothing breaks I have nothing more to learn."

The 2H was meant to be raced in the '68 Can-Am season, the Canadian-American road racing series with the unique unlimited, No-Rules character. The car was the successor to the 2G of '67, an updated aluminum 2E chassis ('66 season), equipped with very advanced aerodynamics, the first one with the high wing. The original 2E was developed in secret, but very close co-operation with Chevrolets Research & Development department.

For various reasons, Jim Hall wanted a radical different concept for the 2H. What he had in mind was a low drag, ultra narrow, streamlined coupe. And: a return to composites again. An advanced plastic chassis so to speak, like the one he developed already in 1963, the Chaparral 2A.

The 2H was a racing car concept the world had not seen yet. Technically and aerodynamically it was totally different. It was the first composite full monocoque chassis ever. The entire chassis doubled as the body shell. Chassis components were fabricated in Pre-preg, a brand new type of glassfiber reinforced plastic. Then the different components were bonded to become one structure. The entire structure was then cured in an oven.

Within the shell a few holes were left for entry, forward vision and a few covers for adding fluids, but that was it. Apart from the thin engine cover, all the rest was stressed.

However, developing the chassis met serious, very serious trouble. The exotic De Dion suspension for example, kept on tearing the composite chassis literally to pieces during tests on Rattlesnake Raceway, the private racing track of Chaparral Cars in Midland, Texas. It was obvious: the 2H was not ready to race at the start of the '68 season. As an in-between-solution Hall ran an updated 2G that season which sadly ended with his massive accident at the last race, the Stardust GP at Las Vegas. The results of this accident added even more stress to the development of the 2H because Jim Hall spend months in a wheelchair. He could test the new car to some extend without braces but he would never drive again at the high level he was used to. So he had to find a driver to race and develop the new car. John Surtees seemed like a logical choice because Surtees was a former Formula 1 World Champion (1964, Ferrari), also former Can-Am Champion (1966, Lola) and on top of that, like Jim Hall, a driver/engineer himself with a very strong reputation.

As it turned out however, 'Big John' had absolutely no confidence in the car and its concept. At Rattlesnake he complained about the horizontal driving position and the limited vision through the side windows and front screen. He demanded the roof being opened so he would sit higher and therefore have a better view at the track. And this is where my suspicion of two 2H chassis starts..

Back to the mystery of the two 2H chassis

It is widely believed that the 2H was the first all Chaparral developed car since the 2A of 1963. General Motors would've had no interference with its development. According to Paul van Valkenburgh however this is not true. He writes in "Chevrolet = Racing..?" that "Chevrolet R&D knew about the existence and development of this car. He mentions "a narrow, low drag, streamliner coupe."

Another quote: "it was only when the terrible problems with the De Dion axle occured that Chevrolet R&D were going to help solve the problems."

And he tells us a lot more:

"I can at least admit my own negative contribution to the 2H. In the summer of 1966, after preliminary road and wind tunnel tests, I had sent drawings of a similar car to Hall, explaining why the low drag design looked good - and then forgot about the whole thing. In the summer of 1967, Hall's chief engineer, another Paul, Lamar, quit, and he hired Mike Pocobello, at that time Chaparral project engineer at Chevrolet. Pocobello was to help Hall engineer his new car, about which Chevrolet was kept relatively uninformed."

In the meantime 2H related development work had been done at Rattlesnake Raceway: taping up the 2F windows to simulate the seating position and the visibility of the 2H and cowling duct work. All this work had been done by the summer of 1967.

And there is another VERY interesting detail: at Chevrolet R&D a similar concept of an advanced plastic chassis had already been tried. In "Chevrolet = Racing..?" Van Valkenburgh tells this story about the design and building of a very peculiar fiberglass chassis:

"After considerable experience with aluminum chassis in R&D, a number of engineers began to feel that Hall had the right idea in his fiberglass Chaparral 2A. Also in five years interim, many new aerospace materials had been made available, such as super-strength directional-weave fiberglass cloths and more rigid epoxy resins. The most exciting development was a pre-impregnated combination of the two, which could be laid up cleanlier and was cured in an oven instead of by catalyst. (Joe) Kurleto was convinced that this was the answer to weight in Hall's chassis and fragility in R&D's, particularly when coupled with an all-new structural design based on previous findings. A year later, the G.S. IV. was a complete tub, and it was crated up and sent to the warehouse. It was the stiffest vehicle frame that had been built. But it was build around the 327 engine, and in the meantime the 427 took over. Because of the carefully engineered structure and integral design, a major revision in all the moulds would have been necessary, and its cost was already well over its budget."

So, now this is a VERY valuable piece of background information. Once again there seems to be the traditional Chaparral-Chevrolet question: who was first? Who discovered the new materials and recognised the benefits in chassis development? Secondly, but far more interesting in relation to my suspicion of the existence of a second 2H chassis, there is this insight information about how difficult it was to change an already executed design with this very specific technique.

The changes that had to be made to the 2H to get the more vertical driving position that John Surtees required must have been far more difficult to realize than simply "opening the top, and put a headrest on" as all the literature tells us. Because of the integrated design and the Pre-preg technique! It would have meant cutting and sawing and plastering, rebuilding and so on. Remember even the dash was integrated as well as the foot well and the seat and the fenders, etc.?

Finally I'm very curious about that G.S.-IV design. Paul simply describes it in his chassis chronology scheme as "fiberglass chassis" without an appearance date where he did so with some other chassis. But he puts it between the Chaparral 2F, appearance date 2/4/1967 and the G.S. IIg (Chevrolet R&D/Chaparral 2G) appearance date 9/1/1968. So it must have been somewhere in the later part of 1967 that this frame was ready.

Paul neither gives information about the specifications of this very advanced frame. Most likable it was a monocoque, probably a sports car or Can-Am type of racing car (since the 327 engine) but if it was fully stressed like the 2H remains unclear. It was however of integral design.

Was this frame perhaps already the prototype of the 2H? And why was it crated up and sent to the warehouse after completion? Van Valkenburgh doesn't mention any test drives. But that occurs very strange to me because Chevrolet R&D had a very hefty testing doctrine in those years. They didn't leave an opportunity unused in that department. And a lot of testing they did at Chaparral in remote Texas.. Furthermore, it could have been worthwhile to test the vehicle, even with the small displacement engine, to get some useful data for an eventual vehicle to come with the big engine (the later 2H?)..

Could this particular Chevrolet chassis have been the car at Rattlesnake Raceway as seen on snap shots in some Chaparral books? And has it been secretly tested there instead of being send to the warehouse? And, when we name this car the Mk 1 for convenience, is the 'Mk 2' the car that was officially revealed to the press in 1969? A second 2H chassis with the top already opened?

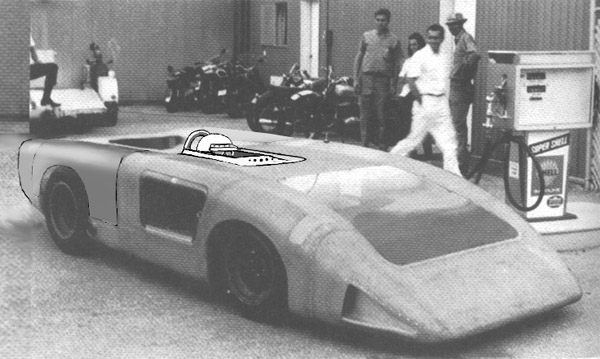

Okay, I hear you thinking: "Nice theory, but where is the proof?" Well, take a close look at these two pictures.

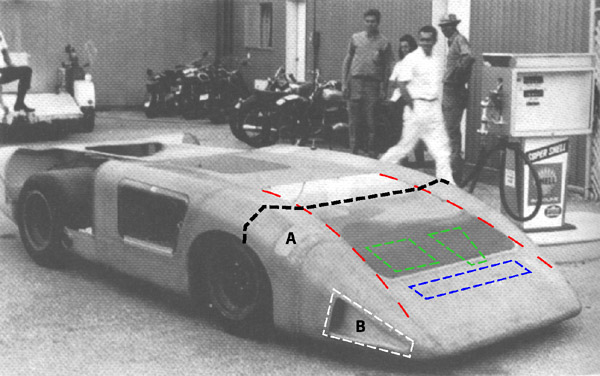

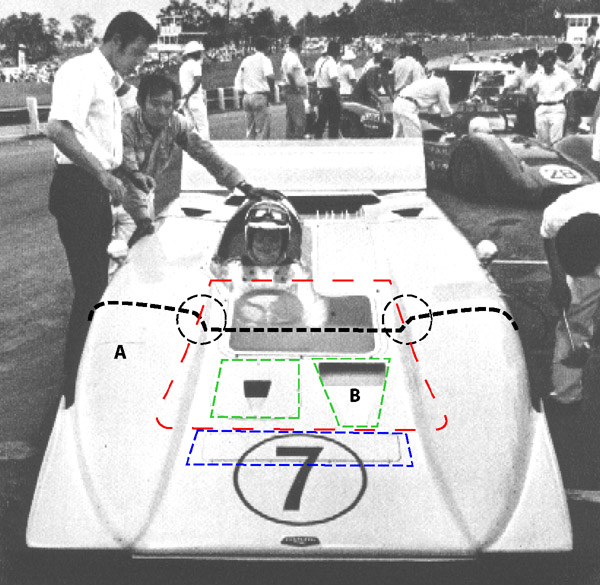

The one above is what we'll call the 'Mk 1'. This is one of the unofficial snap shots, taken at Rattlesnake Raceway, Chaparral home ground. Take a close look at the profile of the transverse section (black dotted line). You will discover a dramatically different shape as compared to the same black line on the 'Mk 2' (below), notably within the little circles. The Mk 2 features a kind of pontoon like design from front to 'amidships'. And look at the shape, although difficult to see, of the little covers (A). Also different. Another big difference lies in the shape of the front screen (the red dotted lines). This window would not fit within the 'pontoons' of the Mk 2. Further, the brake ducts on either side of the body (B) were apparently relocated to the top. And the blue dotted line indicates a flap for air escaping from an inbuilt front wing. A device that was not apparent on the Mk 1.

The one above is what we'll call the 'Mk 1'. This is one of the unofficial snap shots, taken at Rattlesnake Raceway, Chaparral home ground. Take a close look at the profile of the transverse section (black dotted line). You will discover a dramatically different shape as compared to the same black line on the 'Mk 2' (below), notably within the little circles. The Mk 2 features a kind of pontoon like design from front to 'amidships'. And look at the shape, although difficult to see, of the little covers (A). Also different. Another big difference lies in the shape of the front screen (the red dotted lines). This window would not fit within the 'pontoons' of the Mk 2. Further, the brake ducts on either side of the body (B) were apparently relocated to the top. And the blue dotted line indicates a flap for air escaping from an inbuilt front wing. A device that was not apparent on the Mk 1.

So: contrary to the common view of that time, my conclusion is that it was not a matter of 'simply opening the top' after Surtees' request. It was something that was not logic or may be even not possible to do because of the integrated structure and the difficult Pre-preg technique. It required a structural reshape. I believe it must have been a very, very complicated job, if done indeed!

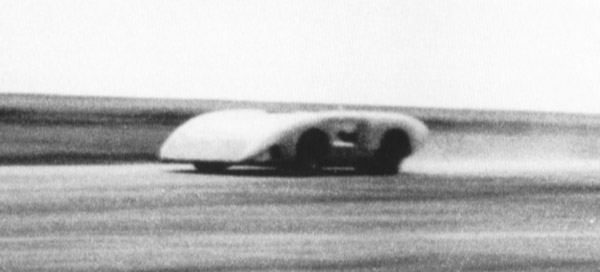

Another important thing adds to my 'two chassis' theory. The 2H was intended to be a pure, narrow streamliner with as low drag as possible. That means: no spoilers, no flaps, no wings, no add-ons sticking in the air. Just the rear mounted radiator, a few NACA ducts and the wheel wells were the only necessary "aerodynamic" holes. Contemporary press confirmed this concept. Quote from an article "The British are coming" (in Car & Driver September '68): "spoilers are unlikely"!

The target clearly was a slippery piece of soap on wheels. Just like it was during the early test runs at Rattlesnake (see rare snap shot below).

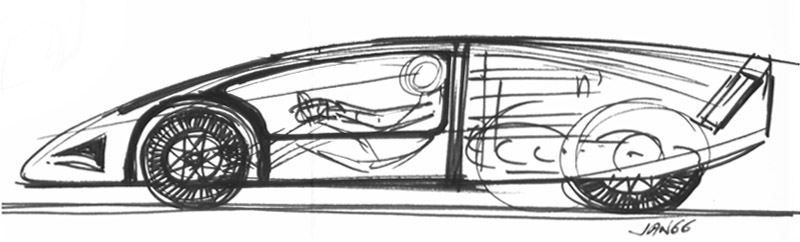

If the Mk 1 had worked out fine during the initial test runs, the operation of opening the top on Surtees' request, could have been very simple. Look at my idea of the concept in the picture below. It would have been matters of just alter the seat a little bit and a relocation of pedal box, shifter and steering system. These are components that simply could be bolted to another place on the structure. And a simple redesign of the (non stressed) top hatch would have done the job. Within this solution, Surtees would have been just peeking out like today's Formula 1 drivers. A small air splitter in front of his nose and a tubular roll bar just behind his head. Although I'm not an aerodynamicist, damage to the aerodynamics (in Jim Hall's words: Surtees' request completely destroyed the aerodynamics) would have been not too big this way I can imagine. May be even negligible. The job could have been finished by simply painting the frontscreen white.

I think however that the concept of the Mk 1 did not work out. Paul van Valkenburgh tells about the fact that Chevrolet R&D had to disapprove the theory of the narrow, low drag concept because in the meantime they had discovered that such a concept would not work. In February '68 Don Cox (another Chevrolet R&D engineer) returned from Midland with a story about the new car and the difficulties met. Chevrolet R&D had to help solving the problems. In essence they had "to disapprove the theory of narrow and low drag". Not low drag alone was the answer to faster lap times but downforce had to be generated. In the sixties that meant: aerodynamic add-ons!

My theory continues: so a second chassis was fabricated (the Mk 2). And.. if the pros of narrowness and low drag could be combined with enough downforce in the corners, the total package could possibly be very effective. So the Mk 2 was equipped with dynamic wings fore and aft, generating so much downforce that the car needed load levelling hydraulic active suspension! That was an absolutely unique feature on a racing car in those days. At the same time the dimensions of the new chassis could be changed to install the more powerful, bigger 427 engine. In other words, a major redesign of the Mk 1. I think it was to be the new and final 2H.

Epilogue

The car saw its racing debut in the Can-Am series, one week after Neil Amstrong set foot on the moon in juli1969. With "astronaut" John Surtees behind the wheel however, it became a very disappointing season. For mainly technical reasons. Everything was too unusual and too complex. An automatic gearbox, a futuristic interpretation of the ancient De Dion axle, new intake manifolds, ultra short wheelbase, extremely narrow track, super wide tires, advanced aerodynamics with dynamic wings and Vortex generators, rear-end radiators, active load levelling suspension and everything in that cramped, composite chassis. Maybe it was a compromise that wouldn't have worked anyhow. The car ended its racing career against a concrete wall during practise of the last race of the season. Surtees had left the team already, frustrated to the bone.

For years, the chassis has been stored at Rattlesnake. In the nineties Troy Rogers restored the car. The 2H (Mk 2?) resides with all other Chaparral models (except the 2C and 2G, which was destroyed in the Las Vegas accident) in the Chaparral wing of the Petroleum Museum in Midland, Texas.

Sometimes it is presented at historic race events. So if you have a change to take a look at this fabulous piece of machinery..

The final questions to Jim Hall

Apart from the questions at the beginning of this article three questions are burning to be answered.

- What happened to 'Mk 1' and were is G.S.-IV today?

- Why had Chaparral to build their own curing oven while there must have been one at Chevrolet R&D already?

- And is the second Chaparral 2H chassis theory to be busted or confirmed?

Jim Hall's answer!

In October 2007 I send this article to Jim Hall to get clearance about this matter once and for all. November 1st I called Chaparral Cars and a kind lady went "to see if Mr. Hall was around and available". To my enjoyment I got him on the phone! We had a very pleasant conversation. Yes, he had read my article. And yes, he had actually seen the G.S.-IV of Chevrolet R&D in those days. He thought it had been a coupe but he didn't know what happened to the chassis.

AND NO: he was sorry to tell that my theory of a second 2H chassis was not right. What I called the Mk 1 is the one and only 2H chassis. But yes, it had been an awful lot of work to change the car to get the driving position John Surtees had requested. So on that aspect I was right. He didn't remember exactly how much time it took however because it was a long time ago. And no: damage to the aerodynamics of he car was not negligible. The damage to the aerodynamics really was severe. Then we had a light conversation about the Goodwood Festival of Speed of 1997 (ten years earlier) were we actually met but he didn't remember me of course. He must have talked to hundreds of people during that weekend! And we talked about Paul van Valkenburgh working at Rattlesnake Raceway and Chaparrals' test work for R&D because of the mild winters in Texas.

I didn't want to take too much of his time but one last thing had to be discussed: my initial plan to have this article published in a car magazine. He said I could do so provided that his answer to the theory would be published too. I promised that and with many thanks I disconnected.

I sat immovable, in silence for a minute or two. The fact that I actually had been connected to Rattlesnake Raceway, Midland Texas, the other end of the world, the place where it all happened, generated rather strong emotions. It overruled my disappointment about the fact that, in the end, my theory wasn't right. Later, I thought about publishing again. But if I were the editor of a car magazine I wouldn't publish a busted theory. So I had to think about an alternative. I toyed with the idea to turn The Chaparral Files into reality. That could be the platform for the 2H article, and some more! Well, here it is.

I hope you enjoyed my story. There are still some (less important) questions left. I hope I'll get the answers in the near future. To be continued?

2H pictures at Rattlesnake Raceway taken from the book: Chaparral by Falconer & Nye.